The Keweenaw State Trail

Some 400 years ago French explorers seeking a northwest passage from the Atlantic through North America to the Pacific followed the Saint Lawrence River through the Great Lakes. We know now that such a passage does not exist, but their quest was not in vain. This raw and wild land would soon be thrust into the world economy.

As a result of this exploration, a trade industry was established with the native people of the area. The French brought their goods (blankets, guns, hatchets, knives, needles, liquor, and cooking pots) in exchange for the extraction of animal pelts, especially the high-valued beaver. The native tribes of the region also revealed other riches of the land: copper, iron, and big pine timbers. The lust for these would change the land forever.

In 1837 Michigan became the 26th state of the Union. A few years later Douglas Houghton published a report on the geology of the Upper Peninsula and specifically described the Keweenaw Peninsula’s copper deposits (secret: it’s technically an island, not a peninsula). Shortly after, the Ojibwe tribe signed the Treaty of La Pointe ceding these mineral-rich lands to the United States. In 1843 the U.S. Government opened a mineral land agency office in Copper Harbor. The Pittsburgh and Boston Mining Company became the first of many to mine the Keweenaw.

Today all the copper mining operations have moved out, leaving only historical sites for us to explore and ponder the past. Some small logging operations are still active in the area.

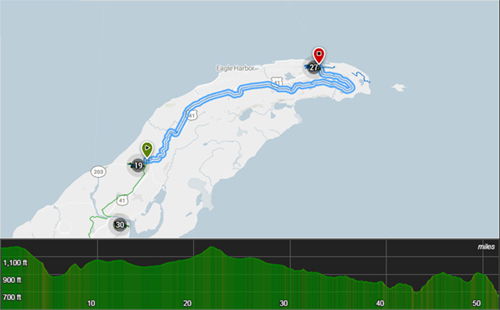

The mining and logging industries established the roads traveled here today. Abandoned railways are now used primarily for recreational purposes: snowmobile and off-road-vehicle trails. These old byways also serve as hiking and biking paths. Chained together they form what we followed as the Keweenaw State Trail, which extends from Calumet to Copper Harbor, a 51-mile trail.

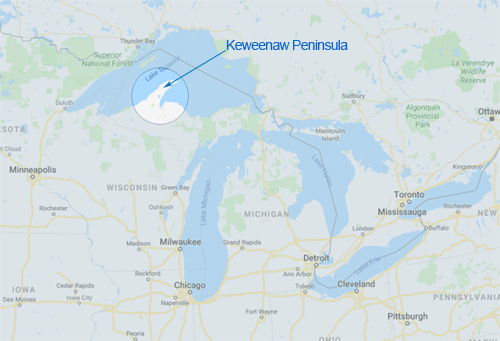

I’ve included a couple maps for those who may not be familiar with the area.

(Credit trail map to MTB Project)

Note from the chart above that the elevation change is minimal – maybe a few hundred feet per hiking day. Being that I just finished hiking the Colorado Trail where a 2000 foot elevation gain is a light day, I’d say the trail is uninteresting from that perspective - essentially flat.

However, the trail is interesting in so many other ways. Anyone who has a thirst for hiking a mild Midwest hardwood and pine forest trail, this is a gem. During mid-week in September the trail is a ghost-town. The summer crowds have left and mid-week is normally low volume for any trail. We didn’t see any other hikers the entire time. We did encounter a few ATVers and a few cars and one logging truck in the later part of the trail – but those were the only other humans.

My nephew, Chris, and I hiked 38 miles of this trail from Vaughsville (15 miles up the trail from Calumet – other signage suggest the old village may be called Vansville; I’m not exactly sure) to Copper Harbor. I had three days to give to this backpacking trip as my time was short and I was busy with other commitments. I just couldn’t squeeze out another day to do the whole trail.

Because we were doing this trail in thru-hiking fashion, we needed to park a car on both ends. Chris was able to park his van at the Fort Wilkins State Park near Copper Harbor and I received permission from the folks at the Vansville Bar along Highway 41/26 to park my Jeep there for a few days – friendly and accommodating people!

From the bar, it’s a short walk down a sandy ATV connector trail to the railroad grade – our trail.

There are signs along this trail for nearby businesses (gas, food, lodging). One curious sign we eventually dubbed the “Petrosexual” sign. For those unfamiliar with the area, the town of Gay is nearby. I could write a few humorous and maybe insensitive paragraphs here, but I’ll just let your imagination play with it.

The trail is a connective string of the railroad grade and a couple less traveled dirt roads. The railroad grade is followed for the first 30 miles of the trail (from Calumet). From here the trail shares Mandan Road until it intersects with Clark Mine Road. Clark Mine Road is followed to Copper Harbor. Both of these roads have no signage indicating their names (except the Clark Mine Road at the Copper Harbor end of the road).

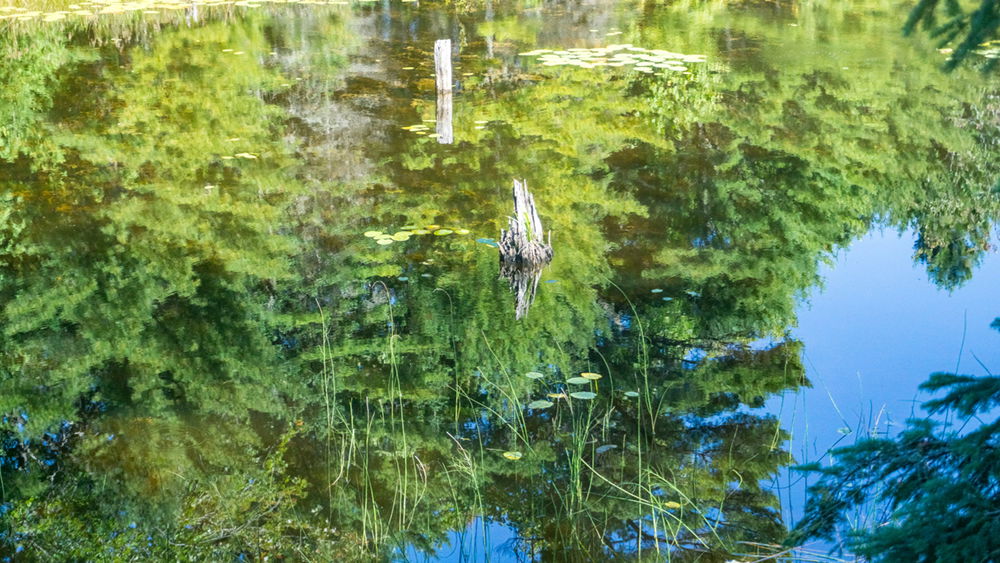

The trail follows and intersects with various creeks, ponds/lakes, and small water cascades/falls. There are no waters to ford; every crossing has a well-maintained bridge. With a little bushwhacking, one could easily explore other lakes close to the trail, like Clear Lake, Addie Lake, Breakfast Lake, Hoar Lake, and several others that are unnamed. However, be aware that much of the property off the trail is private land. So, do a little research before venturing off trail so as to avoid trespassing.

These are the northwoods. The Keweenaw gets upwards of 200 inches of snow fall every winter. Birch trees grow in these parts. And on white birch trees will grow a fungus called chaga. Chaga has been reported to have health benefits, but there are some precautions for its use. I won't go into all that here, except to show you what it looks like. There was evidence that much of the chaga along the roadside had been harvested. This one escaped.

There is very little light pollution due to the very low population throughout the peninsula. This means the stars are incredible and the northern lights are like fire in the sky. I'm not an astro-photographer but here's my attempt at 2am on the second night of our trip to capture some of the stars.

Here are a few other pictures:

Our Camp the First Night

Our Camp the First Night

Chris took claim to his piece of furniture

Chris took claim to his piece of furniture

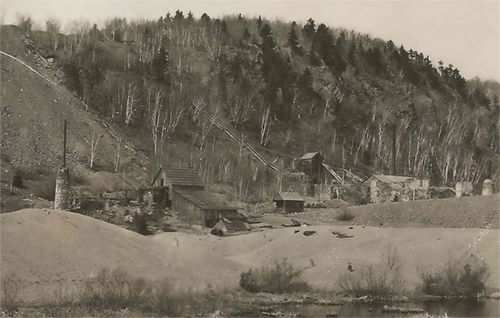

The Clark Mine was a bit off the trail, so we didn't go. But it is thought to be one of the most productive mines of its time in the area.

The Clark Mine was a bit off the trail, so we didn't go. But it is thought to be one of the most productive mines of its time in the area.

Here we are at the finish line on the shore of Lake Fanny Hooe.

Here we are at the finish line on the shore of Lake Fanny Hooe.

As I hiked through this place I couldn’t help but wonder about the lives of the native people of this land – what it took to survive the winters. I thought about the immensity of the task of taking beavers out of these mosquito infested low lands while simultaneously engaging in the necessary diplomacy to arrive at trade deals – an opposite and sometimes opposing skill set. The sheer roughness of negotiating the land required a determined spirit. And the miners and loggers who forged industries from this once untamed wilderness must have been beast-like people; people who on appearance would surely be unapproachable to many today – even those who may still be using some form of the copper and wood products produced back then. I’ve often struggled between the need for mankind to harvest raw materials from places like this and the natural beauty these activities destroy, sometimes forever.

But on the whole, for my part, I resolve to be a good steward, to help others appreciate the beauty around them, and to just enjoy the day. This Keweenaw backpacking trip was just that; it did not disappoint.